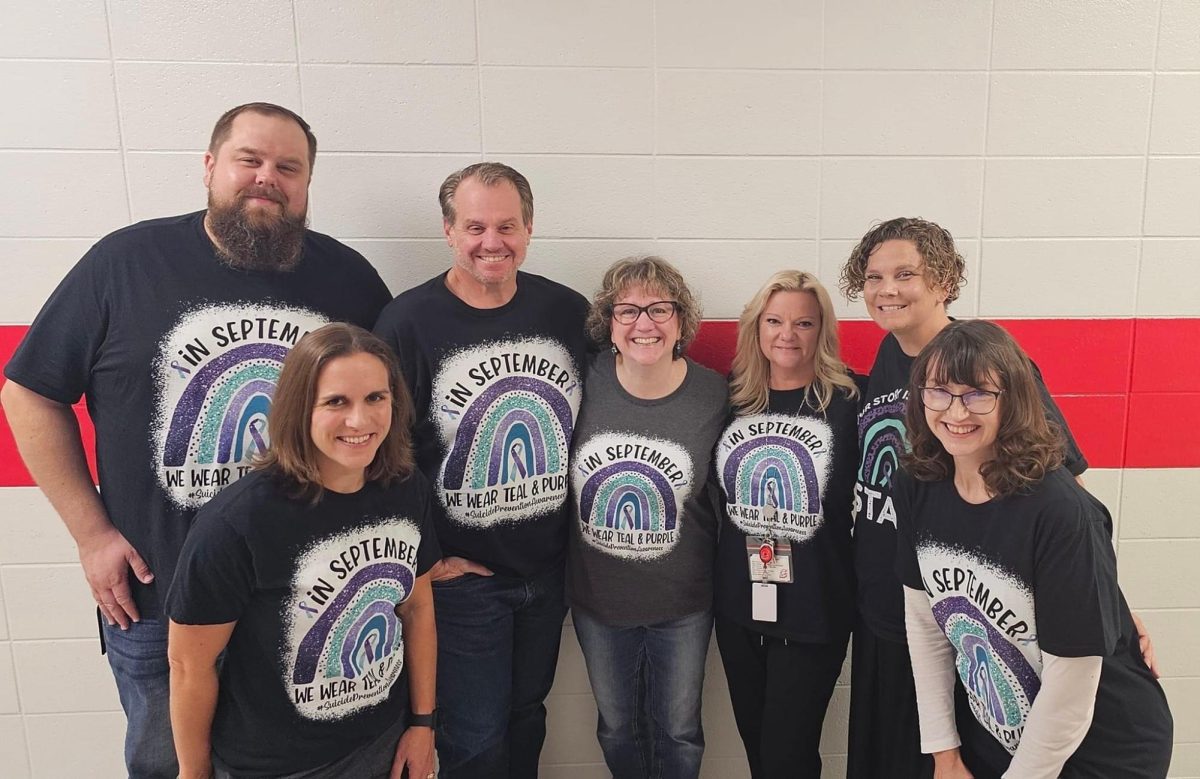

With every turn of the calendar to September, communities emphasize raising awareness for mental health and suicide prevention, an often overlooked and stigmatized topic usually kept in a lockbox in the shadowy back room of society’s concerns.

Senior Emma Watson has experienced a personal loss to suicide. A year and a half ago, Watson lost a close friend to suicide, seemingly out of the blue.

“My friend, February of my sophomore year, committed suicide,” Watson said. “She lived behind me my entire life. She was my babysitter but more than that really. I called her my older sister. I actually figured out about it through a Facebook post. My mom saw on Facebook that her older sister had posted an obituary, and my mom at first thought it was just some horrible joke. When she looked into it, she called me into my room and told me that she had died.”

Since then, Watson has come to terms with the tragedy. Yet still, the pain of losing someone so near-and-dear to her heart — someone she had known nearly her whole life — remains, and it becomes especially apparent during the month of September.

“It is difficult,” Watson said. “I forgot that Suicide Prevention month was a thing, and then, I just saw it everywhere. It just reminds me of her a lot. I think I have gotten past it enough that I look back with fond memories now.”

The fragility of the discourse around mental health and suicide sometimes prevents struggling individuals from coming forward. Watson believes keeping open arms to those who need them is the first of many steps to helping their situations become better.

“A lot of people might see it as a weakness and don’t want to admit to it,” Watson said. “It is hard to talk to other people about it. It is good to have awareness for it and make sure people know that they can get help and that they are cared for. Everyone should think that for the entire year, not just one month out of the year.”

Similar to Watson, English teacher Josh Surface, too, has seen the horrible effects that mental health afflictions have had on those around him. In Surface’s case, the loss came in the form of his former students.

“In the last two years, I had two former students who took their own lives,” Surface said. “Neither of them, of course, were students you could have said, these are two students who are at risk. I would have never identified them as that. I think that further demonstrates to not only me as a teacher but as a person, citizen and community member that mental health is probably one of the most underlying problems that we are not addressing as much as we should be.”

Surface believes his stake comes from a variety of conscious and subconscious tensions concerning the issue.

“As a teacher, it is one of my greatest fears that I am going to lose a student to suicide,” Surface said. “Maybe it is because we feel as though we bear responsibility for our students and that we haven’t done enough. Even when they leave this building, they need to be able to access resources and people that can help them. I am afraid we are losing that a little bit.

While recent years have given the issue more respect and delicacy, Surface believes that more can be done by both individuals and institutions to get help to those who need it.

“We still have groups who don’t take it seriously or who minimize the impact that it has on our students, and really, on our populations,” Surface said. “It is still one of the most pervading factors that impact people on any given day. I’ve seen the devastation it causes on families, friends and fellow teachers, and I think it is something we have to continue getting better at if we are going to address the core issues that exist with our student population.”

To Surface, normalizing discussion of mental health is the first step toward societal improvement around the issue, and it begins at the parental and communal level.

“Getting our parents and community members to buy in that it is a real factor, that it is something that we can do better at if we choose to,” Surface said. “I think that is our biggest decision we have to make – is it a priority for our community? Of course, it should be, but is it?”

Students with mental health afflictions often suffer in silence. They hide their problems until they boil over. Checking in on friends and keeping consistent communication shows these students that others care for them.

“Ask them how they are doing, and do it more than once,” Surface said. “It is not something you ask when they’re only having a bad day. You ask them when they’re having a good day. Showing that you care is important with your friends. Being a confidant is important. They have to know that, and they have to believe it if they’re actually going to talk to you.”

Access to necessary resources for struggling students is another major piece of the puzzle. Establishing these resources has been a part of Center Grove’s response to the problem, but making sure that students know that there are people and places they can go to has been a struggle in the process.

“The school is getting better at addressing those issues,” Surface said. “We have outlets for students. But, do all the students know about those outlets? Are they aware they can go to X, Y or Z if they are having issues? I don’t know. I hope that they know.”

Like Watson, Surface believes the difficulty of dealing with mental health issues in young individuals as well as other population groups stems from a societal stigma around the topic, one that transcends the present and extends from a generational dilemma of years of suppression and negligence toward the issue.

“It is not something that all generations growing up were made aware of,” Surface said. “New information is difficult. If we are not forced to reckon with it we can put it off to the side or on the backburner and say, that is someone else’s problem. We assume we can’t be bothered or touched by these things until it happens.”

Statistics reflect the severity of the mental health crisis in young individuals, particularly on female students. According to the 2023 Indiana Girl Report from the Indiana Youth Institute, which looked at the prevalence of various mental health issues across Indiana high-school girls across the Hoosier state, 47.1% of seventh- through twelfth-grade female students dealt with feelings of depression and hopelessness for two ore more weeks in a row in 2022, and 23.3% of these women seriously considered attempting suicide.

Mental health and thoughts of suicide are an invisible enemy, and yet, they can pervade every minute of an affected individual’s life – a faceless, formless geist that controls their thoughts and emotions but can never truly be seen.

As students say goodbye to the month of September and welcome the true weeks of the Fall, it is important to carry these hard conversations past this single, designated month to bring those shaded ghosts out into the light.

Please find the link to our CGTV Broadcast detailing the resources available to students struggling with their mental health: