Forensics class processes mock crime scenes to end first unit

September 4, 2019

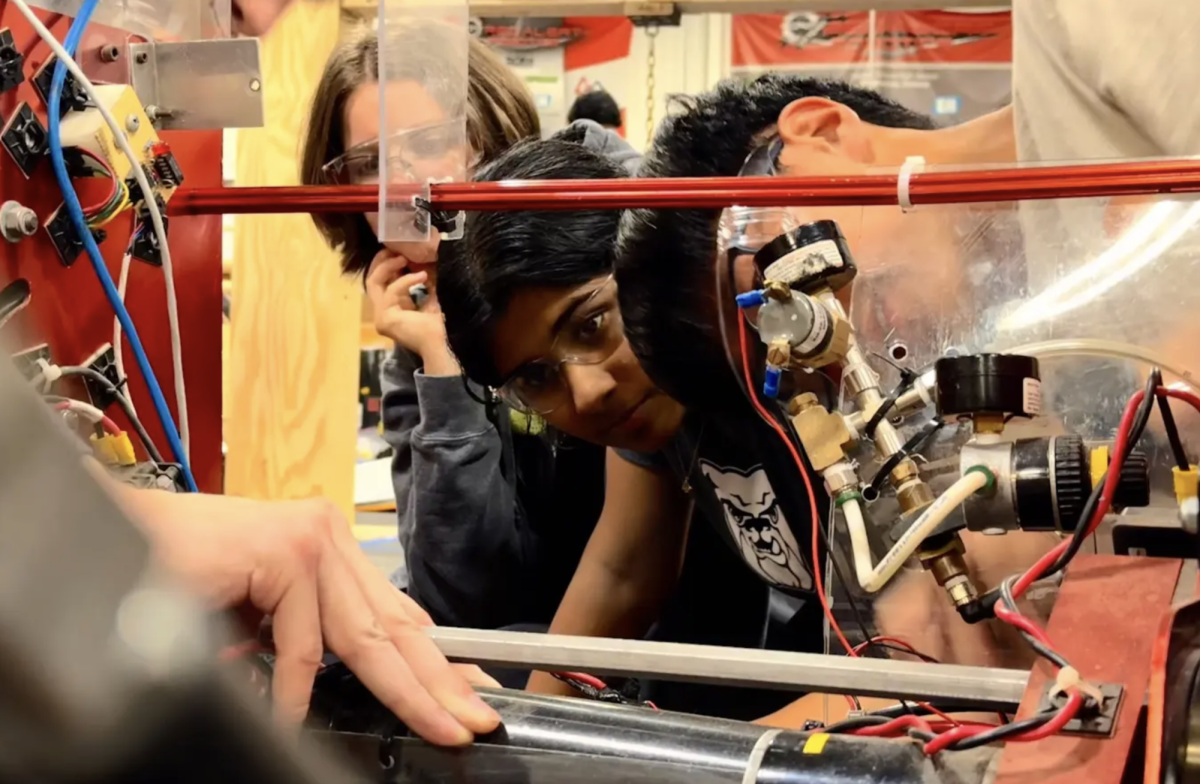

This week, parts of the high school became ground zero for several grisly crimes. Rest assured, no actual crimes occurred. Instead, science teacher Danielle Myers set up multiple mock crime scenes for her Forensics class to process as part of their very own “CSI Units.”

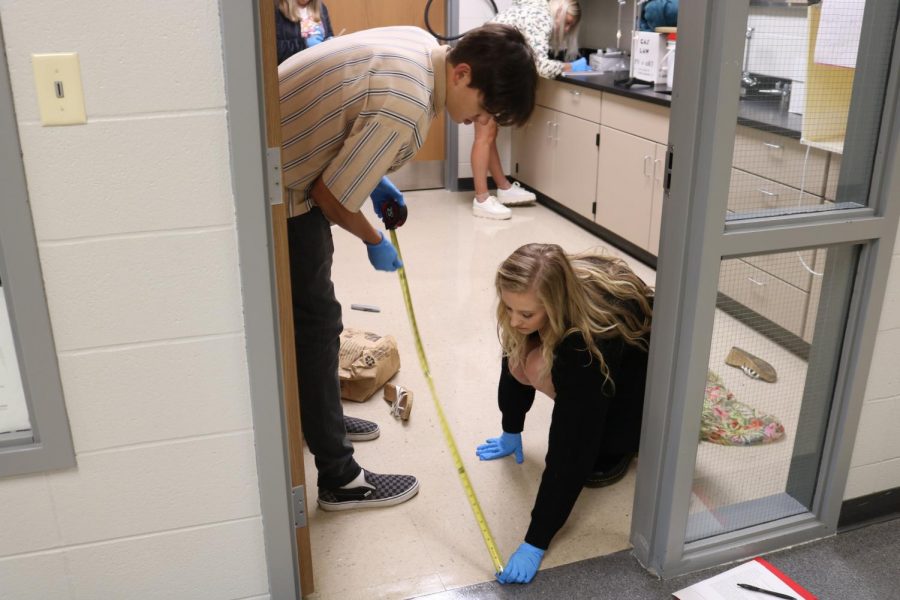

Students had to process an assigned crime scene in one class period. To do so, they used various skills that they practiced beforehand in order to document and process the actual scene. For junior Sophie Culver, this included putting herself in the shoes of an investigator.

“Our crime scene was a sexual assault. We had to go to a different room in the school and walk in completely unaware of what was going on and think about what somebody in that position would do,” said Culver. “We had to take measurements, we had to collect evidence, we had to take notes and do everything that entails [processing] a crime scene.”

These tasks had to be done by the time the bell rang for the next class period. In the last several classes, students practiced on small “table top” crime scenes in order to hone the skills they needed to meet this short – but necessary – deadline.

“We spaced it out using our table top crime scene scenes so that we could learn the process, but often times we’re given a very limited amount of time as a CSI unit to go in and process a scene. We can’t spend days and days on a single crime scene,” Myers said. “You have to be able to make sure that you’re organized, you get in, you get what you need and you get out. The crime scene could be in the middle of a road, so we can’t just cordon that off for hours and hours on end.”

Despite the deadline having been the biggest concern for most students, Myers believed that it could be the part they enjoy the most.

“Honestly, I think that they’re going to enjoy the crunch. They’re going to feel that time constraint and they’re going to be able to identify why what we did with the tabletop was so important,” Myers said. “[We did that] so that they could really get used to what it’s like to photograph and what type of photographs you have to take, and how long it takes to measure a crime scene and how it really does require the entire team working together in order to meet their deadline.”

This window of time was an added stressor to the evaluation, but according to Culver, it did in fact bring her unit together and push them to meet the deadline with even some time to spare.

“There was definitely a lot more pressure since we had 3 or 4 class periods to get [the tabletop crime scene] done and we only had one,” Culver said. “But it was really cool to see how we divided the work up, were able to get all that work done in one period and not be stressed about it and still have fun. We got everything done so it was pretty amazing.”

The teams were comprised of three to four students, and it was recommended that certain jobs be delegated in order to get everything done on time; the most important factor, however, is getting everything done right.

The teams were comprised of three to four students, and it was recommended that certain jobs be delegated in order to get everything done on time; the most important factor, however, is getting everything done right.

“I think the biggest challenge for students will be not missing anything because once the class period ends, their crime scene is done. It’s going to go in and it’s going to get wiped,” Myers said. “So [that means] making sure that they’re taking all the measurements that they need, finding all the evidence that is pertinent in their crime scene, and making sure that it’s collected correctly.”

The scenes range from homicide to a drowning to a domestic disturbance and more, each with different evidence, suspects and locations. Despite the stress and limited window of time, the opportunity to put their skills to the test and get experience with a realistic scene was worth it.

“I thought it was really cool to actually put yourself in the position of what a person in a crime scene would have to do, how they have to act and all the different procedures that they had to take care of,” Culver said.